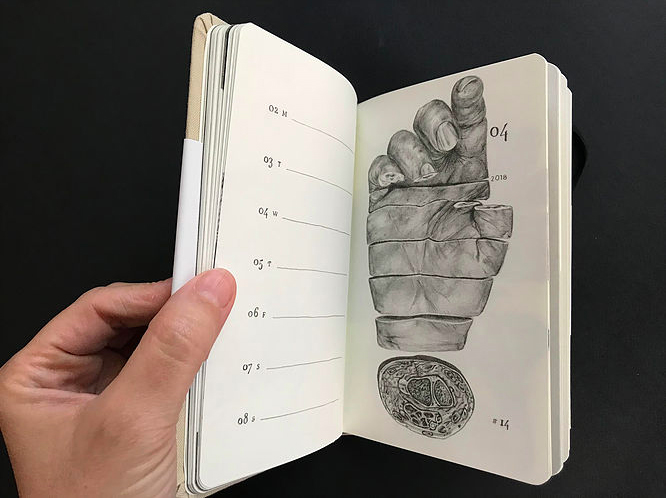

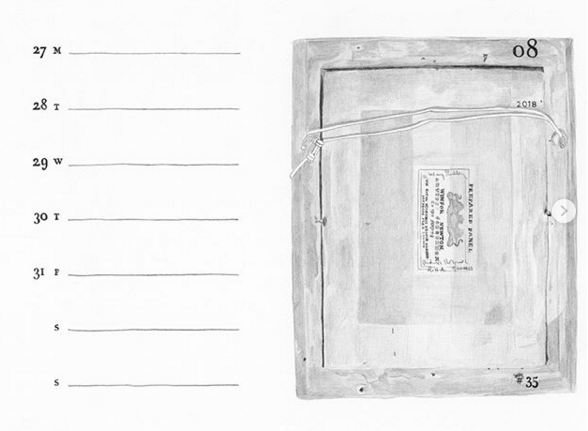

Visiting Maya Attoun’s Charms of Frankenstein exhibition at the Jewish Museum, London, was a curiously disorienting experience. On arrival, you’re asked to take part in an intriguing ritual before you can engage with the exhibition: putting on disposable red gloves. You feel like a curator preparing to handle a delicate object, or perhaps a doctor preparing for surgery. Once you’re wearing the gloves, you are allowed to touch a copy of Attoun’s 2018 artist planner, and take your tour of the museum. You carry the planner with you, held in front of you in a gesture that makes me feel as though I am bearing a gift, offering it to the objects on display. The planner is affixed to a transparent acrylic tray, like an open and portable display case. The exhibition consists of museum objects, each identified with an individual number drawn on a red stone. Each number corresponds to a number in the planner. The museum objects are labelled only with numbers, so have no historical context with which they can be interpreted. The objects are not arranged in any order that I could see, forcing you to actively search for the corresponding number in the planner. And once you’ve found the number, you are confronted not with an explanation or history of the object, but an image. A delicate, realistic, pencil drawing. You are forced to re-orient yourself by making your own connections. For Attoun, it is these negotiations between object and image, artist and viewer, that are as fascinating as the object or image on their own. Her choices of the objects were, in her words, “aesthetic, visual, associative”. The ever-shifting interpretations provoked by bringing image and object into dialogue with each other, which in my mind, tessellate out with every new association, are, to Attoun, like the figure of Frankenstein’s Creature, which shifts with every new translation or retelling. In her conversation with Fiona Sampson, Attoun draws attention to the fact that in being unnamed, the process of creating the Creature is unfinished, and he is constantly being remade.

As Fiona Sampson explained in conversation with Attoun (far more eloquently than I can regurgitate here), when you put one thing in conversation with another, you have not two things, but three things. The drawings in the planner were completed months before the exhibition opened, and Attoun chose objects based on the already-completed drawings. The planner is rejuvenated by being put in context with the objects, much like the process of rejuvenation and (re)vitalisation that occurs in the creation of Frankenstein’s Creature.

For Attoun, the exhibition is an invitation to the viewer to be creative. It’s a unique way of interacting with both art and museum displays, where the only explanatory stories are the ones we tell ourselves. Her choice of objects destabilises the perceived hierarchy of museum objects: an IKEA napkin holder sits alongside a 17th-century figa amulet. This helped to explain the disorientation I felt in being confronted with a museum display stripped of its explanatory labels. Instead, Attoun’s approach gave validity to my own interpretation. I became fascinated with hands in the exhibition, both the exquisitely detailed drawings of hands in Attoun’s planner, and the hands displayed in the museum objects. Hands appear in the planner not just as objects in themselves, but holding other objects. I was aware of Attoun’s hands as they must have been involved in creating these images, and selecting these objects. I became aware of my own hands, turning the pages of the planner to find the appropriate images, involved in the process of interpretation, and mirroring the hands in the drawings. I’ve always had a fascination for the interaction between bodies and objects, and so this was a new way of engaging with museum objects, art objects, and my body’s role in interpreting them. I was constantly in mind of Frankenstein’s Creature as an embodiment of the object-body paradigm: an animated body made up of body parts that at one point had the status of objects.

Objects, planner, drawings: each is woven through with references to Mary Shelley and Frankenstein. Attoun described how part of her process involved rolling herself up (roling herself?) in the character of Mary Shelley. I loved her drawing of the reverse of Mary Shelley’s portrait, the portrait acting at once as a mirror and a means of seeing through Shelley’s eyes. Sampson described Frankenstein as Mary Shelley trying on different roles, as reflected in the different first person narratives: the role of the Doctor (the creator), and the Creature (abandoned and searching). In a way, in her biography, Sampson also takes on the persona of Mary Shelley. For Sampson, words are the shape of a breath. You can’t say more than what can be expressed in a breath. So you can find Mary Shelley’s breath, her life, in her words. I wonder what implications this has for Fiona Sampson’s own words telling the story of Mary Shelley. How the words of the two, the breath and life of the two, are somehow intermingled within her biography. When I read In Search of Mary Shelley (here’s my review) I was captivated and unsettled by Sampson’s creative approach. The presence of Sampson was more obvious to me in the writing than the presence of Shelley. But Sampson explained how, for her, literary biography tends to focus too much on the biography and not enough on the literary. In her biography of Mary Shelley, Sampson wanted to create something readable. Choosing to start each chapter with a scene from Mary Shelley’s life which was fully inhabited, focusing on every visceral detail, was a way of bringing the reader in, using that as a leaping point for the action that follows.

While attending the talk about Attoun’s exhibition and Sampson’s book helped me reorient myself and my understanding of both, I left feeling more comfortable with having been disoriented. Not knowing where I stood in relation to the objects, the drawings, even Mary Shelley’s life, was part of a process of foregrounding my own interpretations and experiences. Next time I visit an exhibition, I’ll be aware that my own agency in interpretation can rely not on being provided with external context, but in the context I bring to the act of interpreting.

Images of Maya Attoun’s work can be found on her instagram and website (where the planner is available to purchase). Fiona Sampson’s In Search of Mary Shelley was published this year by Profile Books. The Jewish Museum‘s current exhibitions, Roman Vishniac Rediscovered and Remembering the Kindertransport run until February 2019.

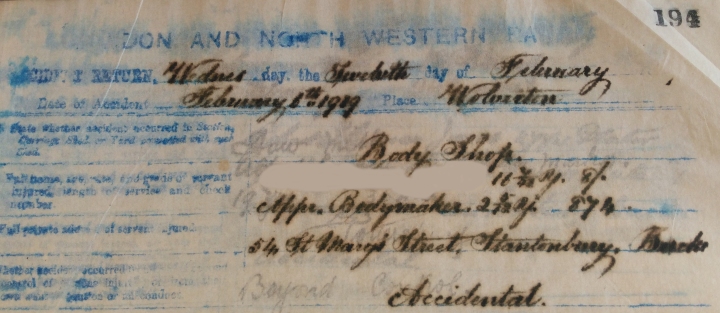

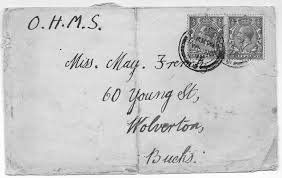

It transpired that the letters were sent by a young man of Wolverton, Albert French, and recounted his experiences as a soldier in the First World War. They were sent to his father and sister, living on Young Street (now demolished, but where Asda is now). Roger was able to find out that Albert was an apprentice fitter between 1913 and 1915 at Wolverton Works. His record card, held by MK Museum, shows he “left without notice” on 16th October 1915. Two days later, he was in London to enlist. While training in Essex, the tone of the letters is clearly optimistic, with Albert writing, “I shall rise like the early morning dew”. But the emotional trajectory of the letters takes a downward turn as Albert makes his way to Belgium and the realities of war sink in. “There are some soldiers who have the opinion that this war will be the end of the world”, he writes. Even faced with the brutal realities of war, Albert seems to carefully guard his feelings from those at home with some careful understatement, “now I’m here I don’t want the war to last too long”.

It transpired that the letters were sent by a young man of Wolverton, Albert French, and recounted his experiences as a soldier in the First World War. They were sent to his father and sister, living on Young Street (now demolished, but where Asda is now). Roger was able to find out that Albert was an apprentice fitter between 1913 and 1915 at Wolverton Works. His record card, held by MK Museum, shows he “left without notice” on 16th October 1915. Two days later, he was in London to enlist. While training in Essex, the tone of the letters is clearly optimistic, with Albert writing, “I shall rise like the early morning dew”. But the emotional trajectory of the letters takes a downward turn as Albert makes his way to Belgium and the realities of war sink in. “There are some soldiers who have the opinion that this war will be the end of the world”, he writes. Even faced with the brutal realities of war, Albert seems to carefully guard his feelings from those at home with some careful understatement, “now I’m here I don’t want the war to last too long”.